The World's First Whale Rosetta Stone

How Scientists Are Using AI to Decode the Secret Language of Dominica’s Sperm Whales.

Editor’s Note: Find out how you can get my new memoir Hell & Paradise as well as over 20 other new nonfiction titles for free at the end of this post.

Now, let’s get into it…

The World's First Whale Rosetta Stone

Dear Permission to be Powerful Reader,

In the waters off Dominica, a miracle is unfolding—quietly, rhythmically, click by click.

For centuries, we believed ourselves to be the only species with true language. Syntax. Grammar. Culture. But now, that myth is dissolving in the deep. A team of AI researchers, linguists, and marine biologists is on the brink of something historic: decoding the complex, structured, possibly combinatorial language of sperm whales.

Yes, language.

Not grunts. Not signals. But potentially an entire symbolic system passed from grandmother to calf like stories around a campfire.

Their language is made of codas—strings of percussive clicks, each one as deliberate as a syllable. One coda may signal a reunion. Another, a warning. Others might be the equivalent of names. Or lullabies. Or laws.

And here’s the astonishing part: they aren’t improvising.

These whales follow grammatical rules.

They modulate rhythm, pause length, even the emotional “ornamentation” of a phrase—just like we do.

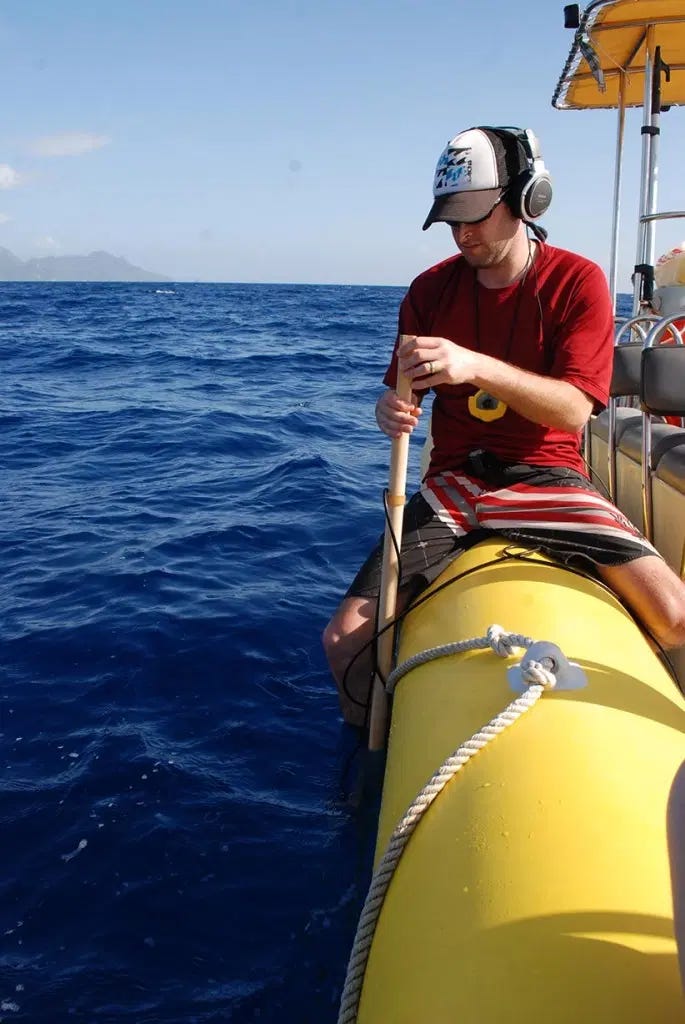

Using arrays of hydrophones, suction-cup audio tags, AI modeling, and drone footage, Project CETI has begun mapping an entire acoustic civilization in the sea.

We are, quite literally, standing at the edge of first contact with an ancient, intelligent, matriarchal species that lives in tight-knit clans, passes on cultural knowledge, and perhaps… talks about us.

And yet—this story remains buried under headlines about gadgets and gossip.

This isn’t science fiction.

This is happening.

We may be the first generation in human history to understand the thoughts of another sentient species—and the last one that ever gets the privilege of a first conversation.

Welcome to the conversation. Welcome to the click-language of Dominica’s whales.

This report dives into the cutting-edge science and heartwarming stories behind decoding the language of Dominica’s sperm whales.

Imagine this.

Somewhere off the coast of Dominica, a grandmother whale drifts beside her calf, sharing the same five-click coda that’s echoed through their family for generations. It’s not random. It’s not instinct. It’s learned—passed down like oral tradition. And now, for the first time in human history, a team of scientists is decoding those sounds with AI. Not just recording them, but actually finding structure. Rules. Patterns. Repetition. Variation. It’s the equivalent of discovering Morse code in the wild—only far more intricate, and spoken by beings with brains six times the size of ours.

The team behind this breakthrough?

They call themselves Project CETI: a coalition of cryptographers, marine biologists, linguists, and machine learning experts. Their mission is simple but seismic—translate the language of sperm whales.

Using hundreds of underwater microphones, drones, suction-cup recording tags, and autonomous robots, they’ve created the largest data set of whale communication ever assembled.

And what they’re finding isn’t just sound—it’s culture.

Meet the Dominica Sperm Whales: Families, Personalities, and Culture

Off Dominica’s coast lives a close-knit community of sperm whale families that researchers have been following for nearly two decadescanadiangeographic.ca.

Dr. Shane Gero, founder of the Dominica Sperm Whale Project, began studying these whales in 2005 and has spent thousands of hours at sea with themusa.oceana.org.

He’s come to know many whales individually – some as long as 18 meters – longer than he’s known his own children1. Each whale is identified by the unique markings on its tail flukes (much like a human fingerprint)wwhandbook.iwc.int.

Researchers give them nicknames that reflect their traits or quirks, helping everyone keep track of who’s who in the ocean family.

One famous family Gero follows is nicknamed “The Group of Seven.” When he first met them in 2005, there were seven membersusa.oceana.org.

Among them is a matriarch named Mysterio and her calf Enigma, whom Gero first encountered when the little whale was only a few months oldusa.oceana.org.

Even as a newborn around 3 meters long, Enigma would stick close to his mother and aunties. As is typical for sperm whales, “it takes a village” to raise a calf – Enigma’s aunt Pinchy often babysits him at the surface while Mysterio dives deep in search of squidusa.oceana.orgusa.oceana.org.

Other relatives like Tweak (another young calf), Quasimodo (an elder aunt with a knobby back), Fingers (a great-aunt with a distinctive fluke shape), and Scar (a half-brother with a scar on his side) round out this family podusa.oceana.org.

Over years of observation, scientists have come to see each whale as an individual personality – playful calves, protective mothers, wise grandmothers – all living together in a long-term social unit.

Sperm whale society is matriarchal and multi-generational. Female whales and their daughters stay together for life, forming what researchers call a social unit of usually 3–20 related individualsspermwhalesdominica.comspermwhalesdominica.com.

The group’s day-to-day life revolves around caring for the young. Just like an extended human family, these whales cooperate: mothers, aunts, and even older siblings take turns watching and playing with calves while others hunt, ensuring the young are always supervised and learningusa.oceana.orgspermwhalesdominica.com.

The bonds are strong – whales have been seen gently stroking each other and spending much of their time in close contact.

Each whale has a role that can change over time (for example, a young female may later become a central babysitter when she’s older and her mother has new calves)spermwhalesdominica.com. The whole family communicates constantly, especially when out of sight in the dark depths.

In fact, for a sperm whale, “being together means remaining in constant contact via sound”spermwhalesdominica.com. This acoustic closeness helps them coordinate dives, share knowledge, and maintain social bonds even when they are hundreds of meters apart in lightless water.

Scientists have discovered that these Dominica whales don’t just have family bonds – they have culture. Each family has its own habits and even its own dialect of click patternsusa.oceana.orgspermwhalesdominica.com.

In other words, whales from one group have signature codas (click sequences) that differ from those used by a neighboring group.

Several families that share a similar dialect form a broader community called a clanspermwhalesdominica.com. Off Dominica, one large clan of about two dozen families is commonly observed, while a second, smaller clan is rarely seenspermwhalesdominica.com.

These clans are akin to cultural or language groups in humans.

The whales learn their specific “accent” from elders: the grandmother and adult females pass on a repertoire of codas (their communication signals) to the calves, much like how human grandparents and parents teach children words and social normsspermwhalesdominica.comspermwhalesdominica.com.

This idea of animal culture – that whales have traditions and learned behaviors – has deeply impressed researchers. “People really resonate with the idea of animal culture,” says Dr. Gero, noting that it opens our minds to viewing these whales as more than instinct-driven beastscanadiangeographic.ca.

They have “their own ways of doing things, their own dialects, and their own cultures,” he explainsusa.oceana.org. In the case of sperm whales, their culture is encoded in sound. To truly know these leviathans, then, scientists must learn to speak their language – or at least decipher it.

Clicks, Codas, and Whale “Words” in the Deep Sea

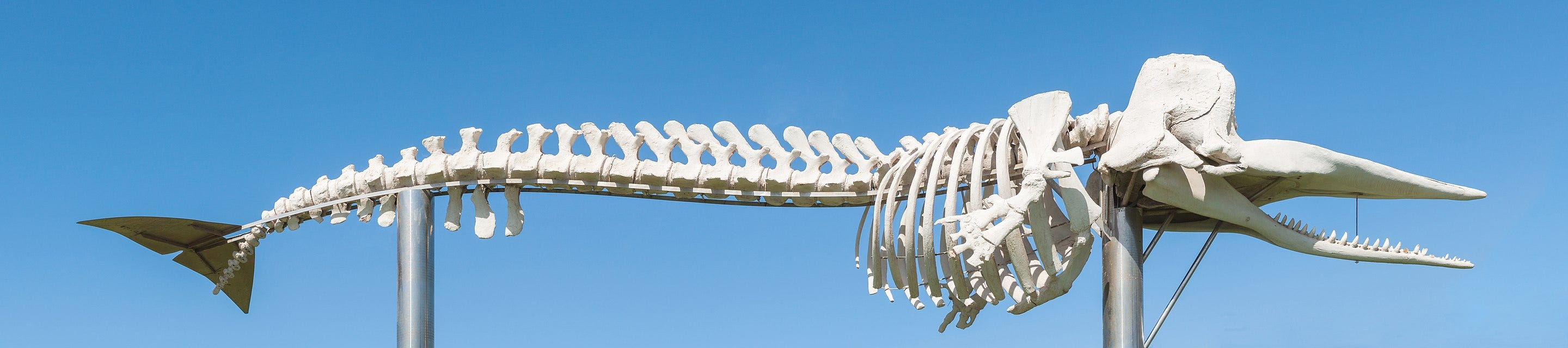

What does a sperm whale “talking” actually sound like? Sperm whales communicate with patterns of clicks.

These aren’t the high-pitched whistles of dolphins or the haunting songs of humpback whales, but short percussive clicks that the whales generate using a powerful sonar organ in their heads (the largest nose in the animal kingdom!)usa.oceana.org.

As Mysterio or Pinchy dives deep into the dark, she sends out trains of clicks to echolocate prey – this is the whale’s natural sonar, “seeing” with sound in a world with no lightusa.oceana.org. But when socializing at the surface or reuniting after a dive, the pattern of clicks changes. The whales exchange slower, structured sequences of clicks – the codas – that appear to be messages for each other rather than for navigationsmithsonianmag.comsmithsonianmag.com.

Each coda is a quick sequence of 3 to 40 clicks, sometimes evenly spaced, sometimes varied in rhythmsmithsonianmag.com. To a casual listener, a coda might sound like someone tapping a code on a drum: “click-click-click… click-click… click-click-click-click”.

Scientists often write them out by timing – for example, a “1-2-1” coda might mean one click, a pause, two rapid clicks, pause, one click. Sperm whales will speed up or slow down the tempo of clicks in a coda (a trait researchers call rubato, like in music), or even add an extra click at the end like an exclamation mark (researchers call this an “ornamentation”)smithsonianmag.com. T

hese changes seem deliberate. One whale can repeat a certain coda pattern, and another whale might answer with the same pattern or a different one, almost like a conversation exchange.

Importantly, these click sequences are not random noise – far from it. Recent research has revealed that sperm whale communication has a complex structure, with rules and patterns a bit like human language. In 2024, a team from Project CETI and MIT analyzed years of recordings from the Dominica whales and discovered a “sperm whale phonetic alphabet.”

They identified 156 distinct coda patterns used by the whalessmithsonianmag.com. Each coda pattern has its own combination of rhythm, tempo, and ornamentation, as if each is a unique “word” the whales can recognizesmithsonianmag.com.

Even more intriguing, scientists found that these codas are built from smaller sound units – the whales recombine a simple set of click elements in different ways to produce their repertoire of codasreuters.comreuters.com. This is similar to how human language works: we have a limited alphabet (or set of sounds) that we combine into an enormous variety of words and sentencesreuters.com.

“All of these different codas that we see are actually built by combining a comparatively simple set of smaller pieces,” explains Dr. Jacob Andreas, an MIT computer scientist on the CETI teamreuters.com. In effect, the whales have a two-level communication structure: at the lower level, certain click patterns act like letters or syllables; at the higher level, those combine into codas that function like words or phrasesreuters.com. And just as humans string words into sentences, whales may sequence multiple codas during social exchanges to convey more complex messagesreuters.com.

This finding – essentially that sperm whales have something akin to words and an alphabet – is groundbreaking. It suggests a level of linguistic richness previously thought to be uniquely human. “The expressivity of sperm whale calls is much larger than previously thought,” says Pratyusha Sharma, the lead researcher of the 2024 studyreuters.com. The whales don’t just make a few simple call types; they have a whole toolkit of sound patterns they can deploy and modify.

For instance, whales will sometimes elongate the spacing of clicks or add a special extra click at the end of a sequence – almost like adding a suffix to change a word’s meaning in human languagereuters.com. The fact that another whale can perceive these fine differences and respond appropriately means they share a common codebook of rules. All this tells scientists that sperm whale communication is highly structured and not just random noisenews.mit.edu.

As MIT’s Dr. Daniela Rus put it, “sperm whale communication was indeed not random or simplistic but rather structured in a very complex, combinatorial manner.”news.mit.edu It’s a bit like discovering that whales have their own Morse code – except far more intricate and versatile.

Of course, humans still don’t speak “whale” – at least not yet. Right now, we have identified the “letters” and many of the “words” of their sound repertoiresmithsonianmag.comsmithsonianmag.com.

What we don’t fully know is what each of those patterns means. Imagine hearing someone speak an unknown foreign language: you might figure out the sentences and grammar, but not the translations. That’s where current science stands with sperm whale codas. Are these clicks naming things (“squid here!”), expressing emotions (“I’m excited!”), or issuing directives (“come closer”)?

We don’t know for sure. Some researchers caution that the clicks might not correspond to a human-like language at all – they could function more like music, setting a mood or strengthening social bonds without specific definitionssmithsonianmag.com.

“It’s possible the noises are more like music, which can have a strong influence on emotions without actually conveying information,” notes Dr. Taylor Hersh, a whale bioacoustician not involved in the CETI projectsmithsonianmag.com.

Still, the structural complexity of codas – and the fact that calves must learn them from elders – strongly hints that information is being conveyed. The whales may be “saying” things to each other about family coordination, identity, or the environment. Decoding those messages is the next big challenge.

Cracking the Code: How Scientists Are Decoding Whale Communication

Understanding sperm whale communication requires a mix of high-tech innovation and old-fashioned detective work.

Early researchers like Dr. Hal Whitehead and colleagues in the 1990s first recognized that sperm whales use codas and even identified regional dialects and social clans. But at that time, our tools were limited to basic underwater microphones and painstaking manual analysis of click patterns. Decoding whale language was like trying to decipher an alien Morse code with pen and paper.

Now, in the last five to ten years, a new generation of scientists has brought cutting-edge technology into the field, launching an ambitious effort to translate “whale speak” on a grand scalecanadiangeographic.careuters.com. Nowhere is this effort more focused than in Dominica, where the resident whale families offer the perfect natural “laboratory” for studyspermwhalesdominica.comwwhandbook.iwc.int.

These whales are relatively accessible year-round, habituated to research boats, and – thanks to projects like Gero’s – already catalogued in terms of who’s who and how they behave. It’s as if we’ve been eavesdropping on a village of whales for years, recording all their conversations; now scientists are finally equipped to start making sense of those recordings.

The flagship project leading the charge is Project CETI (Cetacean Translation Initiative), a nonprofit and interdisciplinary team of biologists, AI experts, linguists, roboticists, and cryptographersen.wikipedia.org.

Launched in 2020 and selected as a TED Audacious Project for its innovative visionen.wikipedia.org, Project CETI’s mission is simple but profound: “to listen to and translate the communication of sperm whales”projectceti.org. Their research is centered in Dominica, working with the very same whales that Gero and others have been observing for yearsprojectceti.org.

What makes CETI special is the breadth of tools and techniques it’s bringing to bear – this is not just a couple of hydrophones in the water; it’s a multi-modal, data-intensive operation, almost like trying to decode an ancient language using every clue possible.

1. Recording the Whale Conversations –

The first step is to gather an unprecedented amount of whale sound data in context. The CETI team deploys a variety of futuristic tools to monitor the whales from every angle. In the ocean around Dominica, they’ve set up arrays of hundreds of underwater microphones that listen 24/7, capturing the clicks from multiple whales at onceprojectceti.org.

By having many microphones spread out (sometimes anchored to the seafloor in a network), they can triangulate which whale is clicking where, similar to how our two ears pinpoint the direction of a sound. This is crucial in group settings – if you hear two whales clicking, the array can tell which individual “spoke” which coda.

At the same time, researchers use aerial drones silently flying above the whales to track their positions and behaviors from the airprojectceti.org.

From a drone’s-eye view, the scientists can see, for example, when a mother and calf separate and how other whales move in, or when a group clusters tightly (perhaps exchanging codas) versus when they spread out to dive. Knowing what the whales are doing while they are clicking is key to interpreting possible meanings.

Additionally, the team uses “D-tags” – small high-tech computers with suction cups – that they temporarily attach to whales’ bodiesprojectceti.org. These tags record sound from the whale’s perspective (everything it hears and says) as well as depth, orientation, and acceleration.

A D-tag lets the researchers virtually ride along as a whale dives, echolocates a squid, or chit-chats with its family. It’s like putting a GoPro on the whale, except it’s an ears-and-motion recorder.

Finally, CETI is even testing autonomous swimming robots that can glide near the whales to observe them up close without disturbing themprojectceti.org. These robot “whale assistants” might carry cameras or hydrophones to follow a whale into the deep, going where researchers can’t. By combining all these tools – hydrophone arrays, drones, tags, and robots – the project is collecting the richest picture ever of sperm whale life and language. They are amassing a giant dataset of audio and video: thousands of hours of whale conversations paired with observations of whale behaviors.

2. Turning Sound into Data (and Pictures) –

Recording the raw sound is just the beginning. The next phase is to process these recordings and visualize the patterns. Whale clicks are so rapid that to the human eye they look like spikes on an audio waveform.

CETI scientists use algorithms to detect and isolate each coda in the recordings, time-align them from the multiple microphones, and then represent them visually. One technique is to create something like a musical score or a spectrogram for each coda, showing the timing between clicks.

The team has developed new visualization tools to highlight differences in tempo and rhythm, making each coda pattern stand out like a unique shapenews.mit.edu. By viewing the clicks this way, researchers can more easily classify codas and notice subtle variations.

They also annotate the data extensively: each recording is tagged with the identities of whales present (thanks to ID catalogs), what each whale was doing (from drones and tags), and environmental context (time of day, etc.).

This annotated, structured dataset is what they feed into their AI modelsprojectceti.orgprojectceti.org. In essence, the team is building a “whale communication database” analogous to a bilingual Rosetta Stone, except we don’t have the translation yet – we just have a lot of whale “texts” with notes on what was happening at the time.

3. Letting AI Learn the Language – The heavy lifting of deciphering patterns is done with machine learning, the same kind of technology behind voice recognition and translation in our smartphones.

The CETI project’s computer scientists train AI models on the trove of whale sound data to find structure that humans might miss. One approach is akin to how we train speech-to-text AI: the model tries to predict what comes next. For example, given the first part of a coda sequence, can the AI predict the likely next clicks or coda, the way predictive text guesses your next word?

If yes, that means it has learned the rules of whale grammar to some extentnews.mit.edunews.mit.edu. The 2024 study did exactly this – they created a “whale language model” after training on thousands of codas, and found that the model could anticipate patterns, confirming that those patterns were rule-based and not randomnews.mit.edunews.mit.edu.

The AI also clusters similar codas together, which helps identify which codas are variants of the same “word” or belong to the same “topic.” For instance, the AI might notice that one group of codas always occurs when calves are playing at the surface, while another group tends to occur during foraging dives. These correlations hint at meaning. Researchers are indeed looking at behavioral context: by using algorithms to match sounds with observed behaviors, they hope to translate codas like X coda tends to mean “let’s regroup” or Y coda means “I’m babysitting this calf now”.

Dr. Gero suspects that many codas help whales coordinate family activities – “I think it’s likely that they use codas to organize babysitting, foraging and defense,” he saysreuters.com. For example, a certain coda might be a signal from an aunt like Pinchy to Enigma’s mom indicating “I’ve got the baby, you can dive,” and another coda later might mean “Come back up now.” The team hasn’t decoded that specifically yet, but those are the kinds of hypotheses they are testing as they link sound patterns to social roles.

The machine learning process is very much one of “venturing into the unknown,” as Dr. Rus describesnews.mit.edu. The AI has no “Rosetta Stone” or translation key given to it – it must find structure purely from the data. That’s why having lots of data is essential: the more whale conversations it hears, the better it can detect statistical patterns and even rare codas.

Project CETI’s researchers have indeed identified dozens upon dozens of coda types (156 so far) through these analysessmithsonianmag.com. Many of these codas are used across different families and even between the two clans, suggesting they form a shared sperm whale “vocabulary.” Yet some codas or variations might be unique to certain groups – perhaps like local slang or family names.

The AI can help map which codas are universal and which are specific. It’s notable that one result from the analysis was that individual whales have distinct “voices.” That is, even when two whales use the same coda pattern, tiny differences in the intervals or pitch can identify which whale said itspermwhalesdominica.com. (This aligns with what human researchers suspected: just as we recognize friends by their voice, whales likely recognize individuals by subtle acoustic signatures). Teaching a computer to detect these differences can allow tracking of who is speaking in large group recordings, adding another layer to understanding the social dynamics.

4. Talking Back (The Future) – The ultimate test of whether we’ve decoded whale language will be to try talking back to the whales. In the future, scientists plan carefully controlled playback experimentsprojectceti.org. This means using underwater speakers to play a recorded or computer-generated coda to a whale and observing its reaction. If we think a certain coda means “come here,” for example, we could play it to a whale and see if it approaches or looks around for another whale.

Project CETI envisions doing this once they are confident in some translations, as a way to validate the AI’s understandingprojectceti.org. It’s a delicate step – after all, we want to be respectful and not confuse or distress the whales. Any “conversation” attempts will be done with ethical oversight and likely start with simple, benign codas (perhaps a friendly contact call that whales use routinely).

The idea is to see if the whales respond appropriately, which would be strong evidence that we have cracked the code for that signal. Dr. David Gruber, CETI’s founder, imagines that one day we might even have underwater robots that can interact with whales in real-time, exchanging codas in the whales’ own rhythm – essentially speaking with them on their termsnews.mit.edu. For now, that remains a dream, but each incremental step – from identifying the “alphabet” to mapping out the coda “dictionary” – brings us closer to itsmithsonianmag.com.

What Might the Whales Be Saying?

While full translation may be a few years away, scientists have educated guesses about the kinds of things Dominica’s sperm whales talk about. Given their social lifestyle, much of their “chat” is likely about keeping the family coordinated and safereuters.com.

They might be sharing information such as “I’m here, where are you?” or “Let’s all dive now” or “Watch the calf, I’ll be back in 40 minutes.” In fact, one common coda that Caribbean sperm whales use is a pattern of five evenly spaced clicks – researchers suspect this might be a general contact call that says “we’re a group” or helps them recognize each other’s clanusa.oceana.orgspermwhalesdominica.com. (In the Pacific, different clans have their own signature call – a strong hint that codas can serve as identity or group markers, akin to a surname or a club handshake among whales.)

Other codas might be used in specific contexts: for example, a rapid-paced coda exchange often occurs when two groups meet at the surface, possibly an excited greeting or an introduction sequence. Slower, spaced-out codas sometimes occur during gentle socializing, which could be more intimate “conversations” within the group.

Mothers and calves also have their own acoustic interactions – a calf might produce a small burst of clicks and the mother replies with a reassuring coda, essentially the whale version of a parent and child calling back and forth to stay connected in a crowd.

One especially heartwarming possibility is that whales use unique calls for individuals – perhaps the equivalent of names. Researchers have observed that each whale can be identified by its click patterns, and individuals have slightly different “accents”spermwhalesdominica.com.

It’s conceivable that a particular coda sequence is often used when, say, Enigma is directing a call to his aunt or when a mother summons a specific calf. If whales do have name-like signals, it would mean they have a concept of individual identity encoded in sound, which is a hallmark of advanced communication (dolphins, for instance, are known to have “signature whistles” that function like names).

The Dominica team is actively looking for such patterns – they have decades of records of who was present and who responded, giving clues to whether certain codas are tied to certain whales.

Beyond family coordination, whales might talk about food and threats. Sperm whales dive thousands of meters to hunt giant squid and fish, and usually only one or a few from a unit dive at a time while others babysit at the surface.

It’s possible that when a foraging whale returns to the group, it shares some information – perhaps a coda that could mean “I found good hunting over that way” or “Let’s move east, not much food here.”

This is speculative, but in other species like honeybees, complex communication about food locations exists. Sperm whales could similarly inform each other about fruitful feeding zones or warn of dangers (like an approaching orca). In one observed instance in Dominica, whales made a particular pattern of intense clicks when a pod of orcas (killer whales) was nearby – was it a warning call? The researchers took note, and future analysis may confirm if that coda consistently appears around predators. Such findings would be akin to decoding specific words like “predator!” in the whale lexicon.

As the CETI project proceeds, one major task is to match vocalizations with specific behaviors and contextssmithsonianmag.com. The team is using statistical models to see, for example, if Coda A always precedes a group dive, or if Coda B is only heard during calf playtime. If they find a strong correlation, that coda likely pertains to that activity. It won’t be a word-for-word translation like “We will now dive to 800 meters to hunt squid” – whale communication might not be so literally descriptive – but it could be a signal like “all together now” (to coordinate a dive) or “reassurance” (to keep contact).

Diana Reiss, a marine mammal communication expert, notes that even if we don’t get a direct human translation, linking whale sounds to behaviors would be “an amazing achievement” because it shows understanding of their intentsmithsonianmag.com. It’s a bit like deciphering that a dog’s bark means it wants to go out – you’ve learned the functional meaning even if it’s not a “word” in human terms.

Through these analyses, scientists hope to answer big questions:

Do sperm whales have questions or answers in their communication?

Do they tell stories or just convey immediate needs?

Is there gossip in a whale pod?

We don’t know, but their complex social life suggests their “conversations” could be rich.

As Dr. Gero mused, discovering what whales talk about would “speak to an internal life in a being that’s so different from us” – a window into the mind of a whalecanadiangeographic.ca.

Already, the work has challenged the long-held notion that sophisticated language is uniquely human.

“I suspect we will find many patterns, structures and aspects thought to be unique to humans in other species, including whales, as science progresses,” Gero says, “and perhaps also features of animal communication which humans do not possess.”

reuters.com In other words, whales might have communication abilities that we haven’t even imagined, potentially even innovations in language that humans don’t have. After all, their environment and needs are very different from ours, and their communication evolved to suit a deep-sea, dark, three-dimensional world of soundreuters.com.

Why This Matters: A New Understanding of Intelligence and Life on Earth

The effort to decode sperm whale language is more than a scientific puzzle – it’s a journey that could transform how we see other animals and ourselves.

These Dominica whales, with their immense brains (the sperm whale brain is the largest on the planet, about six times heavier than ours)projectceti.orgreuters.com, live in complex societies that parallel our own in surprising ways: they have tight-knit families, regional cultures, lifelong bonds, and possibly even names and dialects.

Recognizing that their clicking vocalizations may carry intricate information forces us to acknowledge that intelligence and communication are not human exclusives.

Sperm whales diverged from us on the evolutionary tree some 50 million years ago, and ever since they’ve been charting their own path toward social complexity and perhaps symbolic communication. If we confirm that their codas amount to a true language (even if a very different kind than human language), it will reshape the way we think about the very concept of language.

We might have to broaden our definition of language to include patterns of clicks in the ocean

Jellybean49 / Getty Images

From a philosophical and ethical standpoint, decoding whale communication blurs the line between humans and other creatures.

It’s one thing to know animals are smart; it’s another to actually understand their thoughts (as communicated).

Imagine for a moment that one day we decode a series of codas and it translates to something like, “Strange boat nearby, be cautious,” or “How is your calf today?” It would be a profound moment of connection – like making first contact with an alien civilization, except the aliens have been alongside us on Earth all along.

In fact, the CETI scientists often draw this parallel explicitly. “One of the intriguing aspects of our research is that it parallels the hypothetical scenario of contacting alien species,” Pratyusha Sharma says. “It’s about understanding a species with a completely different environment and communication protocols… decoding a naturally evolved communication system within their unique biological and environmental constraints.”news.mit.edu.

The sperm whales are, in a sense, “aliens among us” – highly intelligent beings in the ocean depths, with a form of communication we are only starting to grasp.

Successfully decoding their messages would be like finding a Rosetta Stone for interspecies communication.

offering insight into the mind of another intelligent lifeform.

There are also practical implications for conservation. Sperm whales are currently classified as vulnerable to extinctionsmithsonianmag.com. They are still recovering from the ravages of whaling in the 19th and 20th centuries, and today face new threats like ship collisions, entanglement in fishing gear, noise pollution, and climate changesmithsonianmag.com.

Understanding what sperm whales are saying could directly help protect them. For instance, if we learn to recognize a distress call or a call that indicates the presence of danger (like a loud ship engine or lack of food), we could use that knowledge to mitigate harm – such as adjusting ship routes or detecting when a group is in trouble.

Moreover, as Smithsonian Magazine noted, “if researchers knew what sperm whales were saying, they might be able to come up with more targeted approaches to protecting them.”smithsonianmag.com

We might also engage the public more deeply in conservation: drawing parallels between whale communication and our own language could help people see whales as kindred intelligent beings, deserving of empathy and protectionnews.mit.edu.

Indeed, Roger Payne’s discovery of humpback whale songs in the 1970s (and sharing those songs with the world) famously helped spark the “Save the Whales” movementnews.mit.edu.

Likewise, if the world hears that sperm whales have conversations and family call-outs, it might inspire a stronger push to safeguard their habitat. Dominica, for example, has already moved to create the world’s first sperm whale sanctuary (a marine reserve) in its waters, effective January 2025canadiangeographic.ca – a testament to how much these whales mean to the local community and scientists. Knowing their “language” would cement the case that these creatures are irreplaceable treasures.

Finally, this research is a celebration of human curiosity and technological ingenuity. It combines the age-old wonder of observing animals (think of a young David Attenborough enthralled by whale sounds) with 21st-century AI and robotics.

It’s a story of humans trying to cross the boundary of species by using both heart and mind – the empathy to recognize whale mothers and calves as having lives not unlike our own, and the intellect to design algorithms to decode their signals.

The interdisciplinary nature of CETI – bringing together linguists, biologists, computer scientists, and even cryptographers – underscores that understanding animal communication is one of the greatest puzzles we can tackle, akin to deciphering an ancient script or communicating with extraterrestrialsnews.mit.edu. It pushes the frontier of what we consider possible in understanding non-human intelligence.

Conclusion: A Conversation Begins

On a calm afternoon in Dominica, the sun begins to set as a sperm whale family reconvenes after a series of deep dives. The ocean’s surface is glassy when suddenly – click-click-click-click-click! – a rhythmic chatter breaks the silence. It’s the five-click coda, a familiar refrain among the clan. From a research boat a few hundred meters away, scientists recognize it immediately and smile; it’s as if the whales are saying “We’re still here, all together.” A hydrophone records the exchange, while a drone captures the playful moment a calf nudges its aunt.

For us listening through our instruments, it’s entrancing – not random noise, but a structured, purposeful conversationnews.mit.edu. We still don’t speak their language, but we know enough to realize they have one.

Efforts to decode the sperm whales’ codas have brought humanity to the edge of an incredible breakthrough. Each new piece of the puzzle – a discovered pattern, a predicted behavior, a successful translation of a signal – is like learning a word of a long-lost language. Bit by bit, the veil is lifting on what these majestic giants have been saying under the waves. Will we one day hold a conversation with a sperm whale? The scientists are cautious but hopeful.

“There’s a lot more research to do before we know whether it’s a good idea to try to communicate with them, or even if that will be possible,” admits Dr. Andreasreuters.com. These whales owe us nothing, and as Gero humbly points out, we shouldn’t presume they want to chat with humanscanadiangeographic.ca. And yet, simply knowing that meaningful communication is happening among them is awe-inspiring on its own. It tells us that we share this planet with other intelligent, social, sentient minds that have stories of their own.

Standing on the deck of a boat at dusk, listening to the fading clicks of a sperm whale family as they drift into the blue, it’s impossible not to feel a sense of wonder.

The Dominica whales have opened our eyes to a richer understanding of life – one where a whale’s clicks might be as nuanced as our speech. Like a real-life David Attenborough narration, we can imagine the gentle cadence: “In the hidden depths, the sperm whales speak – and at last, we are learning to listen.”

The conversation has begun, and it is teaching us that language, connection, and culture are woven through the fabric of the natural world, stretching across species boundaries.

In decoding the language of sperm whales, we are, in a way, decoding a new part of ourselves – discovering what it truly means to communicate, to be intelligent, and to share our planet with minds unlike any we have known before. The next time you hear of whales in the distance, consider that they might be telling epic tales of the sea to each other. And thanks to the dedicated scientists in Dominica and around the world, one day we just might understand those talesnews.mit.edunews.mit.edu.

🐋 P.S. Want More Like This?

If this story moved you… if it cracked open something quiet and ancient in you…

Then Permission to Be Powerful was written for you.

Inside the VIP area, you’ll find essays, forecasts, trainings, and tools that go way deeper than what I post publicly. We explore the fractures in the modern world, the secrets behind attention, power, and pattern recognition—and how to navigate it all with more clarity, agency, and emotional depth.

And right now, you can try VIP free for 30 days. No risk. No catch.

See what’s waiting for you:

🔐 The ADHD X-Factor – The hidden edge inside chaotic minds (like yours and mine)

🧠 The AI Prompt Bible – 70+ blueprints to turn ChatGPT into a strategist, therapist, and creative partner

💥 The Trillion Dollar Swipe File – The persuasion secrets hidden in old-school direct response

🎯 The Monster Method – The 8-line email formula that outperformed full funnels at Tony Robbins

🔥 The Trigger Workbook – Emotional reprogramming from the inside out

This is the stuff I don’t share anywhere else.

Raw, deep, and built for people who feel too much and want to do something about it.

👉 Try VIP free for 30 days

Come inside. Listen closer.

The world is speaking. Are you ready to hear it?

Until next time,

Anton

Permission to be Powerful

P.S.: I got together with some author friends and decided to give away our books for free. That’s right. You can get my new memoir, Hell & Paradise, and over 20 other nonfiction titles for free. Check it out here.

💥 Best for a Gut-Punching Power Read

Hell and Paradise by Anton Volney

A fierce, high-voltage wake-up call about truth, survival, and what happens when you finally give yourself permission to be powerful. 🔥

(Yes, that’s you. And yes, it’s making waves.)

🧠 If You Want More Clients

Get More Clients by Lynn M. Whitbeck

Get More Clients is a short, easy-to-read book that walks you through simple, proven tips to close more sales and grow your business.

🔮 For the Meditative & Mindful

The Presence Inner Work by Diego Simon

A calming, spacious read that feels like a long exhale. Great for inner work and visualization.

👻 Dark & Gritty

No Dogs in Philly: A Cyberpunk Horror Noir by Andy Futuro

Grit meets glitch. Think Blade Runner meets Stephen King. If that combo excites you? Dive in.

🤓 For the Writers in the Room

A Writer's Guide to Deeper Stories by Thaddeus Thomas

Masterclass in emotional depth and layered storytelling. A must-read if you’re crafting powerful narratives.

🧩 Nostalgic & Wholesome

My Old Memory Pieces: 1950s Golden Age Everyday Life

A cozy, slow-sipping cup of tea in book form. Takes you back to a time when life felt simpler (at least on the surface).

🍵 For The Self Help Junkie

Self-Care Isn’t Selfish by Jenny Lytle, BSN, RN

The compassionate nurse's step-by-step guide to personalized stress relief.

🧘For The Spiritually Minded

How to Attain Eternal Peace by Pranay Saha

Mastery over the self, transcend illusions of mind, connect with universal consciousness, and achieve deep inner peace

Sources:

Gero, S. – Dominica Sperm Whale Project & personal accountsusa.oceana.orgusa.oceana.orgusa.oceana.orgusa.oceana.org

International Whale Watching Handbook – Whale identification and research in Dominicawwhandbook.iwc.intwwhandbook.iwc.int

Sharma, P., Andreas, J. et al., 2024 – Nature Communications (Project CETI findings)reuters.comreuters.comreuters.comsmithsonianmag.com

Reuters (Dunham, 2024) – “Scientists document remarkable sperm whale ‘phonetic alphabet’”reuters.comreuters.comreuters.com

MIT News (Zimmer, 2024) – “Exploring the mysterious alphabet of sperm whales”news.mit.edunews.mit.edunews.mit.edu

Smithsonian Magazine (Kuta, 2024) – “Scientists Discover a ‘Phonetic Alphabet’ Used by Sperm Whales”smithsonianmag.comsmithsonianmag.comsmithsonianmag.com

Project CETI – Mission and approachprojectceti.orgprojectceti.orgprojectceti.orgprojectceti.org

Identify the Whales (spermwhalesdominica.com) – Whale social structure and clansspermwhalesdominica.comspermwhalesdominica.com

Canadian Geographic (Gero interview, 2023) – Whale culture and Project CETIcanadiangeographic.cacanadiangeographic.ca